Movements Transformed

University activism in the post-Vietnam Era

On January 23, 1973, President Richard Nixon announced the United States and North Vietnam had signed an agreement to end the war. Two months later, the last US combat soldier left Vietnam. The end of the war was bittersweet. While Americans were relieved to see an end to the draft and the mounting list of the dead, the US’s defeat after nearly 30 years of brutal war left so many wondering what it was all for.

When soldiers returned home there was not a sense of triumph as there was after WWII, but for the first time in the country’s history, an overwhelming feeling of defeat. By this point, revelations such as those from the Pentagon Papers (1971)—which revealed how the public was mislead about the war and US aims in the conflict—had deeply affected trust in the government.

Cover of the New York Times marking the end of the Vietnam War, Jan. 24, 1973.

Cover of the New York Times marking the end of the Vietnam War, Jan. 24, 1973.

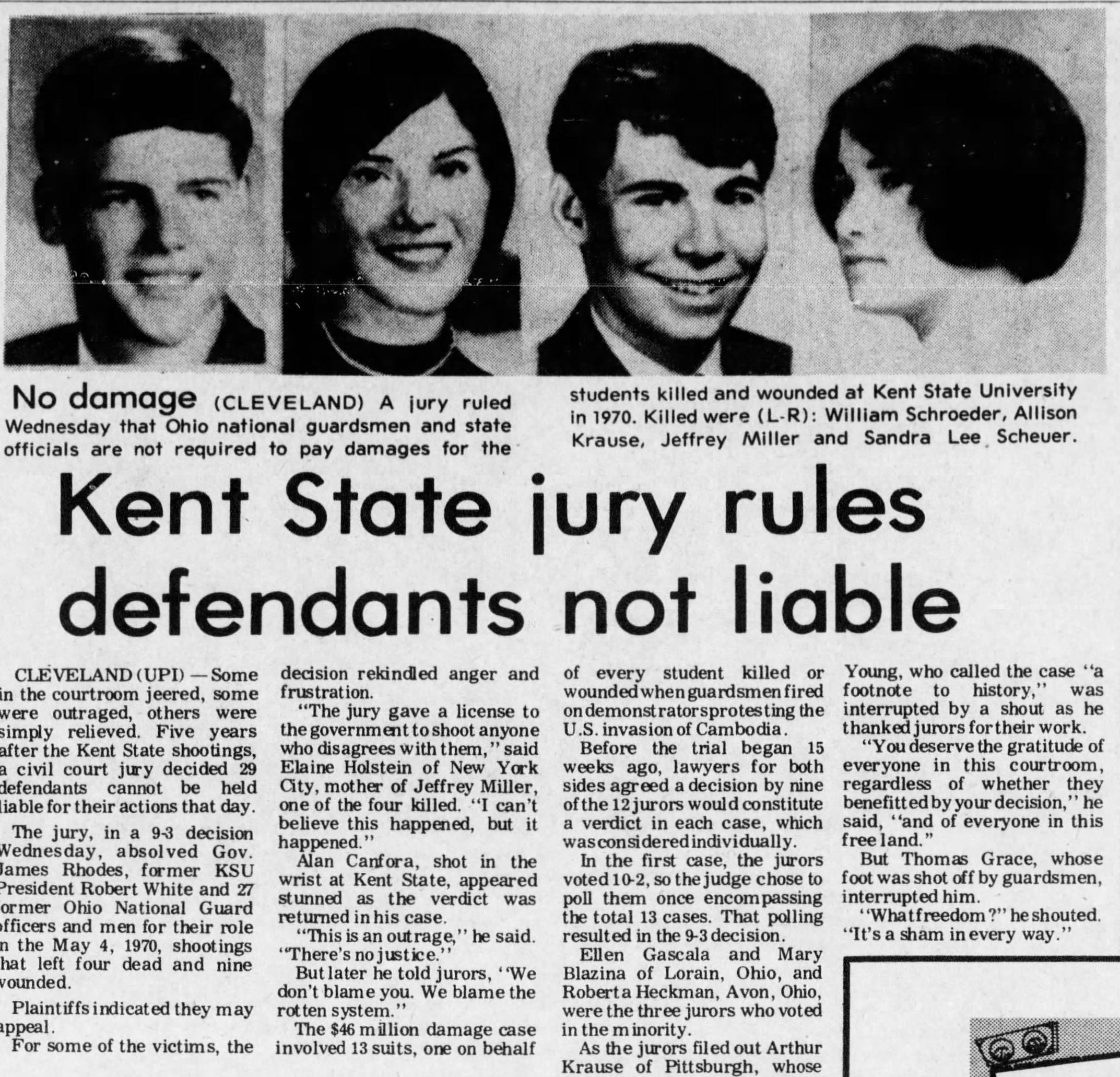

Headline on the acquittal of the Ohio State National Guard on all charges. Shenandoah, Pennsylvania Evening Herald, August 28, 1975.

Headline on the acquittal of the Ohio State National Guard on all charges. Shenandoah, Pennsylvania Evening Herald, August 28, 1975.

The following year, on November 9, 1974, the eight former Ohio National Guardsmen who shot and killed students at Kent State were acquitted by a Federal Court judge. According to Judge Frank J. Battisti, government prosecutors failed to prove “beyond a reasonable doubt” that the guardsmen willfully intended to deprive the students of their civil rights.

After the acquittal, many activists felt despair. The lack of justice for the four students who were slain was a shocking blow to many, most of all the families of the victims. After the verdict, Arthur Krause, whose daughter Allison was among those killed, said, “I still want the truth out, and it didn't come out here.”

“The jury gave a license to the government to shoot anyone who disagrees with them. I can’t believe this happened, but it happened.”

Turning the Energy Elsewhere

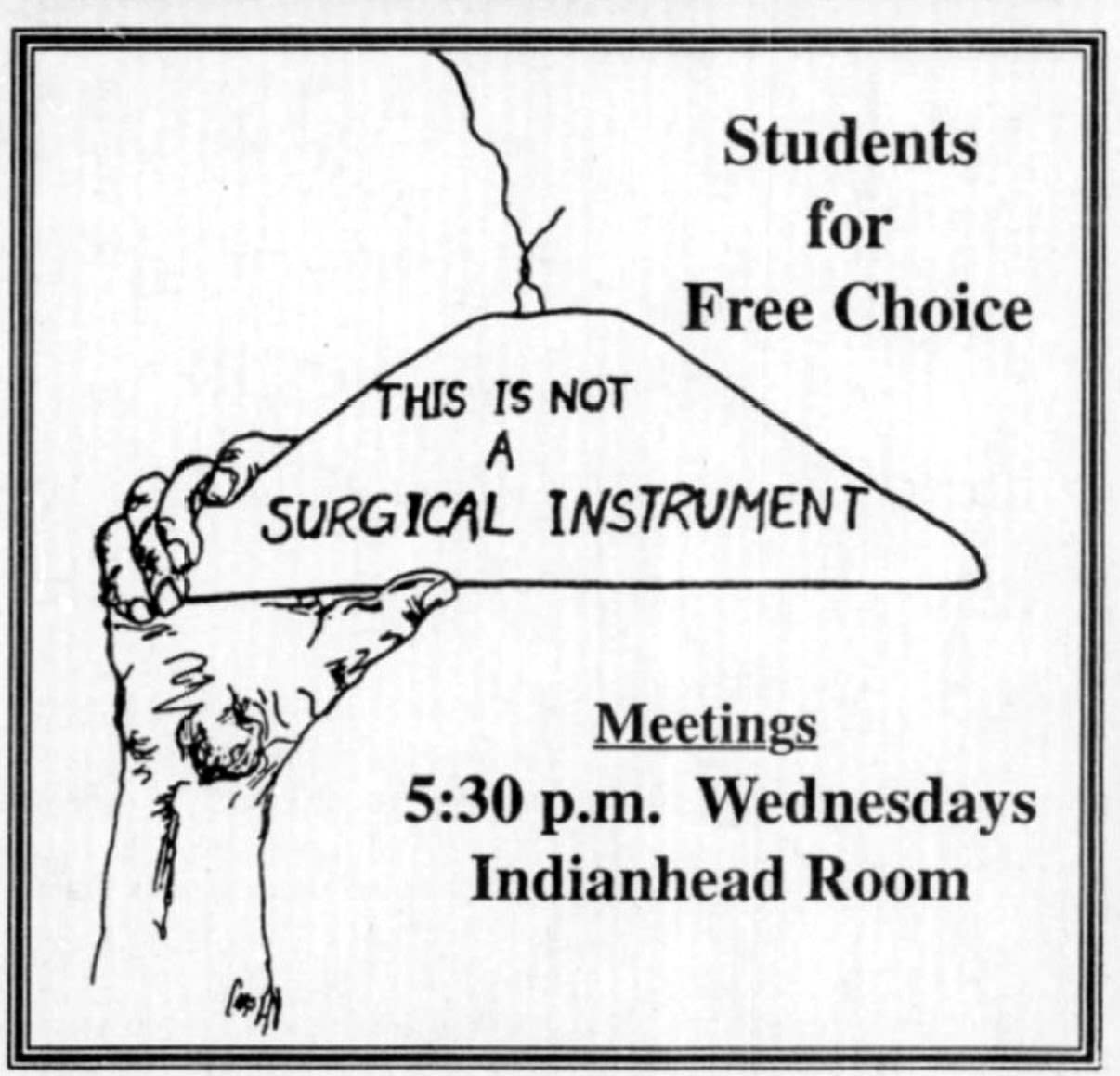

After 1975, the anti-war movement at UWEC started to transition much of their energy toward issues found domestically. This included women's reproductive rights. The 1973 Supreme Court decision in Roe vs. Wade gave women access to safe and legal abortions. However, those who opposed this right rallied to revert laws to past restrictions. Organizations such as “Students For Free Choice” or SFFC responded by spreading awareness and providing a safe forum to discuss the topic of abortions. UWEC had a chapter of SFFC that was responsible for holding discussions and publishing editorials in “The Spectator” UWEC's newspaper.

Not only were students concerned about issues of reproductive rights, but also about a new, terrifying sickness that by the mid-1980s was sweeping across the country: AIDS, or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, an illness that left thousands of people dead, some just weeks after diagnosis. At the outset, many believed that AIDS was only a concern for those living in larger metropolitan areas, a belief that led many in Eau Claire to think it was not a concern for those in rural communities in WI. But, as Ann Langel, managing editor The Spectator wrote in 1985, “It seemed... like something ominous that couldn’t hit here, but two people have died from it in Eau Claire county. It’s not funny anymore."

Another tragic misconception widely believed in the early AIDS crisis was that the disease would only affect Gay communities. Unfortunately, politicians on both a local and national level often reinforced these uninformed and inaccurate views.

"AIDS proliferated itself in the gay community… it’s easier to blame homosexuals, we are already discriminated against, so why not put the blame on us?"

- Anonymous UWEC student in an interview with the Gay-Lesbian Organization, The Spectator, September 1985

College campuses like UWEC became hotbeds for activism and awareness of the AIDS/HIV epidemic. Student groups at UWEC such as the Gay-Lesbian organization, as well as campus offices such as Health Services held Events and community meetings to educate and inform the public about practicing safe sex.

Intellectual Climate

Activism on the UWEC campus did not end with student involvement, but also included faculty. During the Vietnam war, UWEC Professor of History Dr. Steve Gosch was a vocal critic of the war. After the war's end, Gosch continued to speak openly on some of the difficult truths of the war, which—through revelations like those exposed in the Pentagon Papers— had since been revealed to the public. The University's Forum Committee also welcomed many speakers who spoke on controversial topics, including the Vietnam War and the Israel and Palestine conflict.

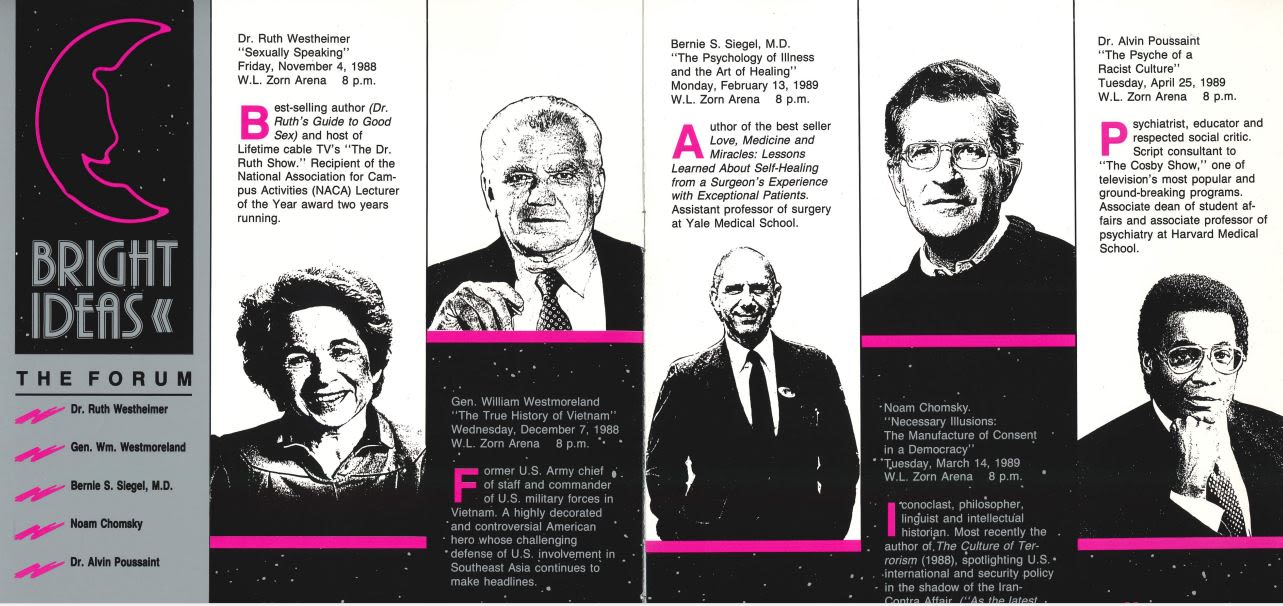

Catalog of UWEC's Zorn Arena guest speakers highlighting multiple controversial political figures in 1988. Steve Gosch Files.

Catalog of UWEC's Zorn Arena guest speakers highlighting multiple controversial political figures in 1988. Steve Gosch Files.

Remembering the Past

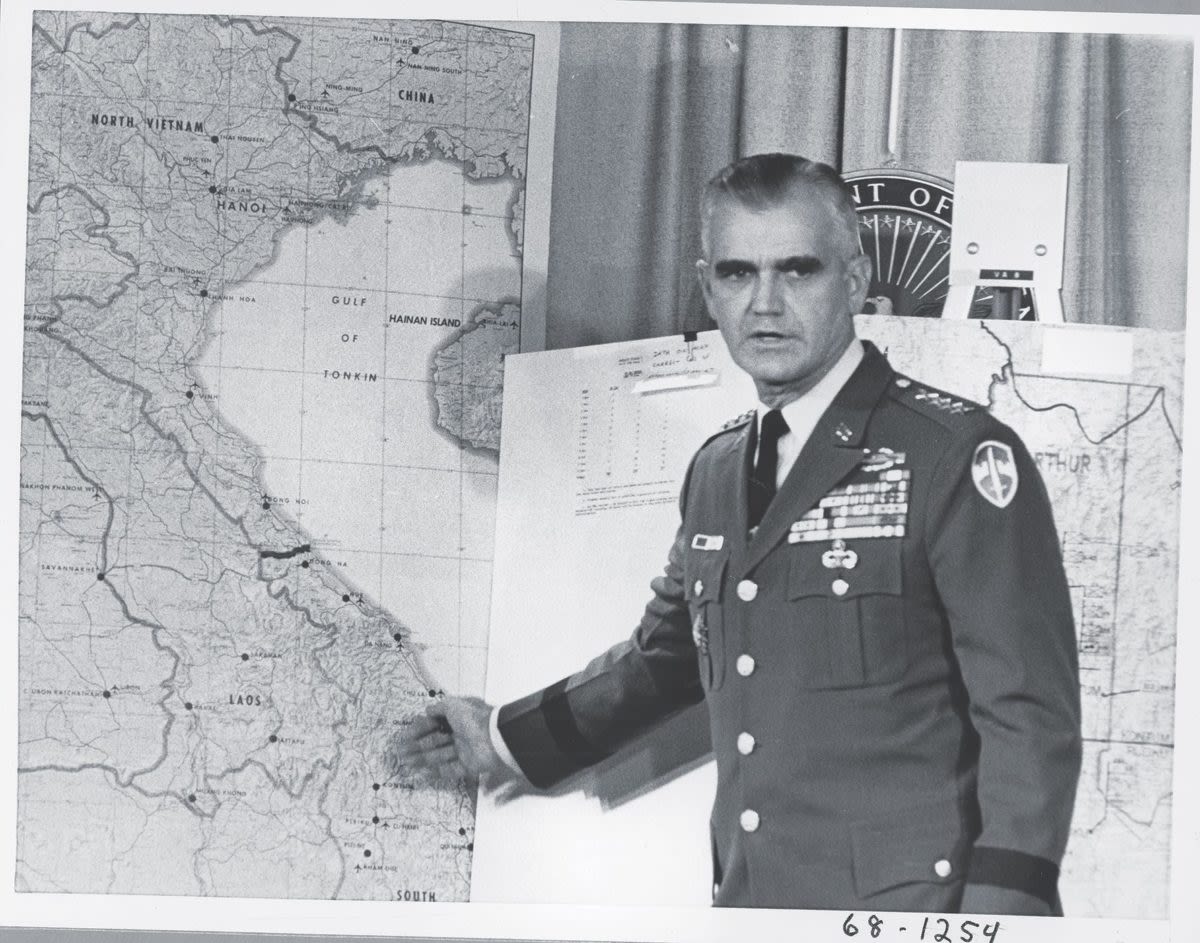

In 1988, General William Westmoreland, commander of U.S. forces during the Vietnam War, came to campus for a presentation titled “The True History of Vietnam.” During the event, Gosch interjected to fact-check certain claims Gen. Westmoreland presented, sparking outrage among some at the event.

In a letter, one attendee condemned Gosch for his interruptions. In response, Gosch stood behind his disagreements not only with the war, but also the push to erase the painful aspects of this history for the nation.

“I am proud of my efforts to end a profoundly immoral and deeply destructive war. I only regret that we in the antiwar movement could not find a way to be more effective sooner.”

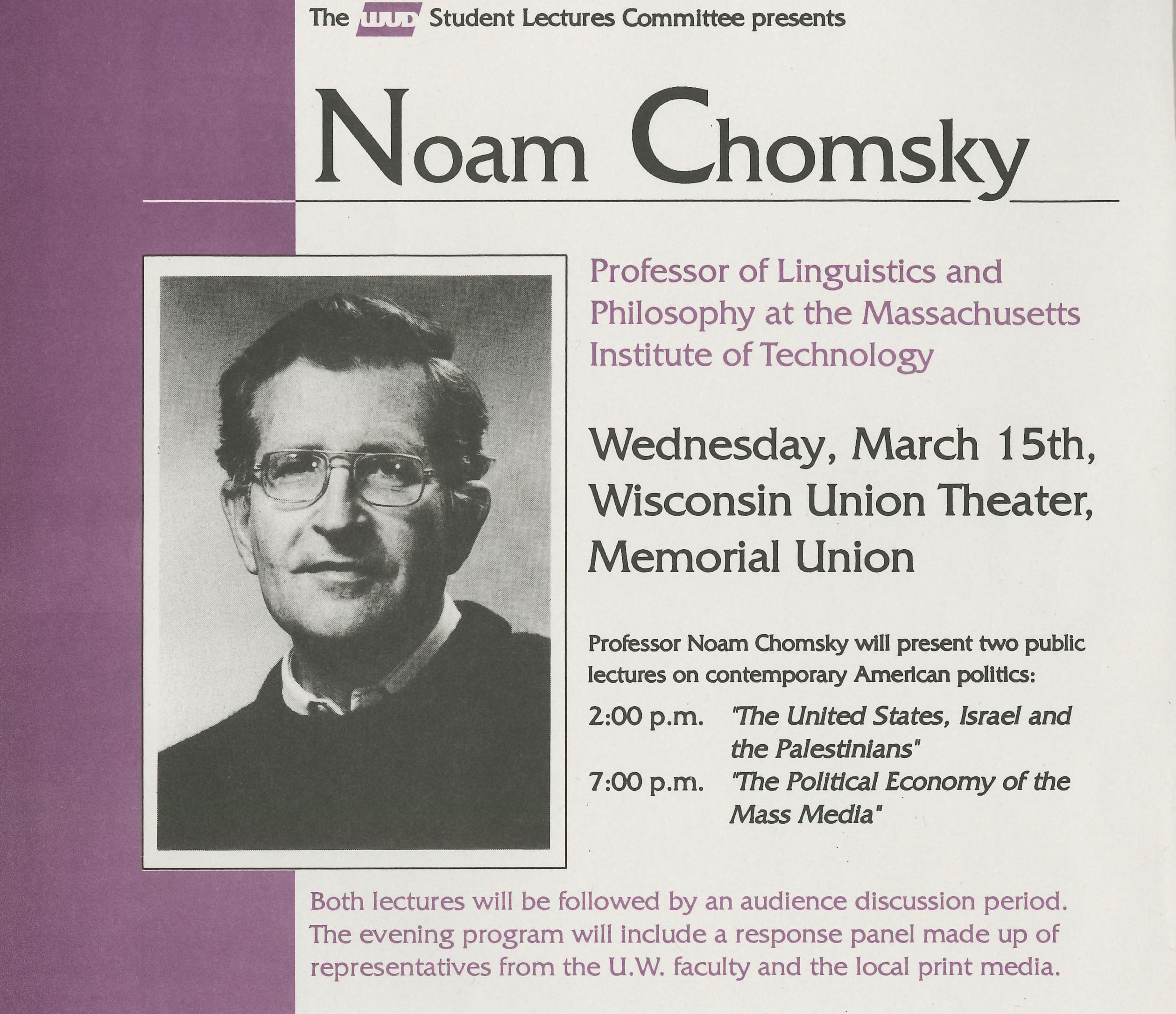

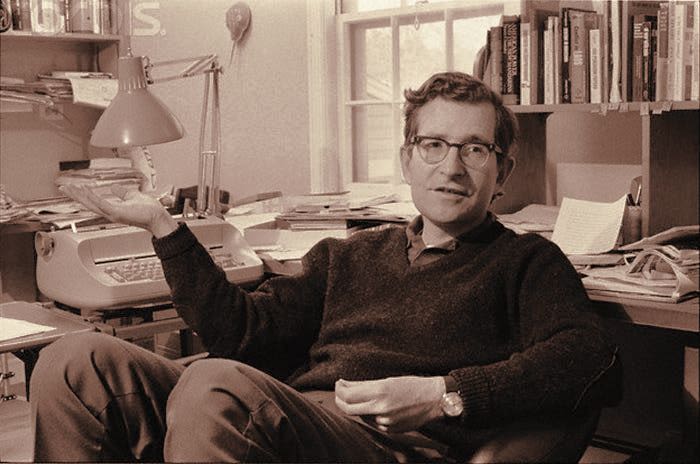

Flyer advertising Noam Chomsky's talks at UW-Madison, after his presentations at UWEC.

Flyer advertising Noam Chomsky's talks at UW-Madison, after his presentations at UWEC.

“Chomsky’s visit and the Chomsky seminar are an example of a liberal arts education efforts at freeing the individual from the though systems that compete for my loyalty. In the process, I have gained a sensitivity to the human spirit and a greater understanding of my own humanity.”

UWEC English Major Paul Lukawski, on his experiences attending Chomsky's talks. Steve Gosch papers.

Open to Debate

Dr. Gosch often encouraged debate among students and faculty at UWEC on relevant national and global issues. He was integral in bringing Noam Chomsky—a professor of philosophy and linguistics who has written more than 150 books on topics ranging from war, politics, genocide, and international affairs—to campus for a series of talks in 1989.

At the UWEC and UW-Madison campuses, Chomsky presented on titles ranging from "The Manufacture of Consent in a Democracy," "The United States, Israel and the Palestinians," and "The Political Economy of the Mass Media." Both students and faculty thanked Dr. Gosch for his efforts to encourage free speech and intellectual debate on the UWEC campus.

The Counterculture in Arts & Events on Campus

A Continued Awareness

While the Vietnam era had come to a close, the sentiments of the counterculture continued in different forms on the UWEC campus. This was most visible in student protests, political organizing, and associations, but also emerged in the arts and popular culture.

One clear thread that emerged was an embrace of multiculturalism. In the 1970s, various student organizations such as the Native American Student Nationalists and the Black Students Association formed at UWEC.

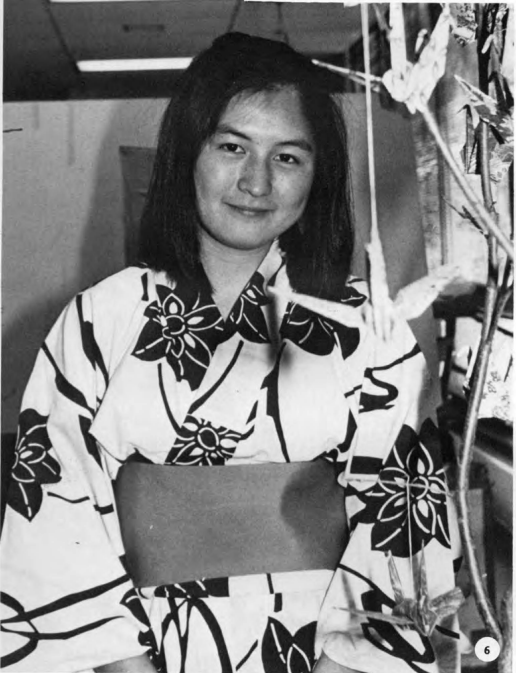

A student poses in traditional Japanese dress for the annual Folk Fair in 1985. (From the UWEC yearbook Periscope, 1986. Courtesy of UWEC McIntyre Library Special Collections and Archives)

A student poses in traditional Japanese dress for the annual Folk Fair in 1985. (From the UWEC yearbook Periscope, 1986. Courtesy of UWEC McIntyre Library Special Collections and Archives)

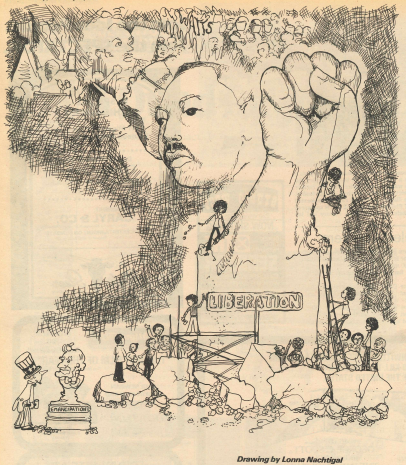

A drawing from the Feb 1974 issue of The Spectator. UWEC McIntyre Library Special Collections and Archives.

A drawing from the Feb 1974 issue of The Spectator. UWEC McIntyre Library Special Collections and Archives.

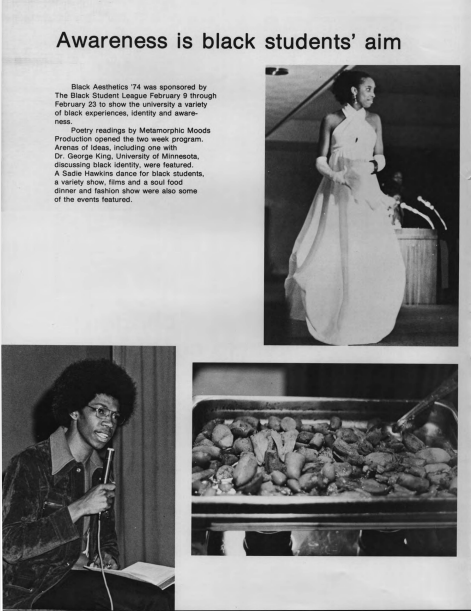

Poetry readings, food, and a dance were all part of Black Aesthetics ‘74. (From the UWEC yearbook Periscope, 1974. Courtesy of UWEC McIntyre Library Special Collections and Archives.)

Poetry readings, food, and a dance were all part of Black Aesthetics ‘74. (From the UWEC yearbook Periscope, 1974. Courtesy of UWEC McIntyre Library Special Collections and Archives.)

Celebrating Diversity

These groups were an opportunity to fight injustice or ignorance through education and community. Members hosted events, advocated for new classes, and led to the creation of community resources like the UWEC Multicultural center. Speaking to The Spectator in February 1974, Secretary of the UWEC Black Student League Karen Sweeney called the new campus multicultural center "a place to join together."

Another event which became an annual staple was the Folk Fair (now called CultureFest), where students of various backgrounds were invited to teach and represent their national cultures. These groups not only took part in advocacy work but also created events that were fun and engaged students through art.

"All the black wants from the white is understanding us as human individuals."

—UWEC Student Gailden Chase, The Spectator, February 1974.

Continuing Causes

StudfedentActivism in the 21st Century

While the efforts of activists at UWEC to seek an earlier end to the Vietnam War and justice for the victims of Kent State did not materialize, campus activism in the decades that followed clearly did not fade away. This remains the case today, where students are active on campus and in the community, raising awareness of issues important on both a local and national stage.

Today, UWEC students remain active advocates for various causes including LGTBQ+ rights, social justice, women’s rights, and political expression. On campus, student groups such as the Black Student Alliance, Latinx Student Alliance, and The Bridge give voice to Black, Latinx, and LGBTQ+ students and the issues they face.

Following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police in May 2020, UWEC students and the Eau Claire community spoke out against racism and injustice, marching for the cause of Black Lives Matter. In the ensuing years, students have remained active in the movement.

In addition, UWEC students are politically engaged voters, hosting events for candidates for major elections and supporting the highest voter turnout rate of all the UW campuses.

“That’s what we’re out here for: institutional change.”

In 2023, for the sixth consecutive year, the nationwide Campus Pride Index rated UWEC as one of the top institutions in the country for creating a safe and welcoming environment for LGBTQ+ students. UWEC is one of only 30 four-year campuses to achieve this top score on the Campus Pride Index.

Efforts on behalf of students, faculty, and administration have been integral in creating this inclusive and welcoming environment.

“Queer students across the country are seeking out universities where they feel supported, seen and celebrated for who they are as LGBTQIA+ people, and I’m immensely proud that they are able to find that here.”